studio stories

BUILDINGequity

A candid panel discussion identifies intersections and frameworks to support equity efforts in architectural practices and processes.

BY JENNICA DEELY

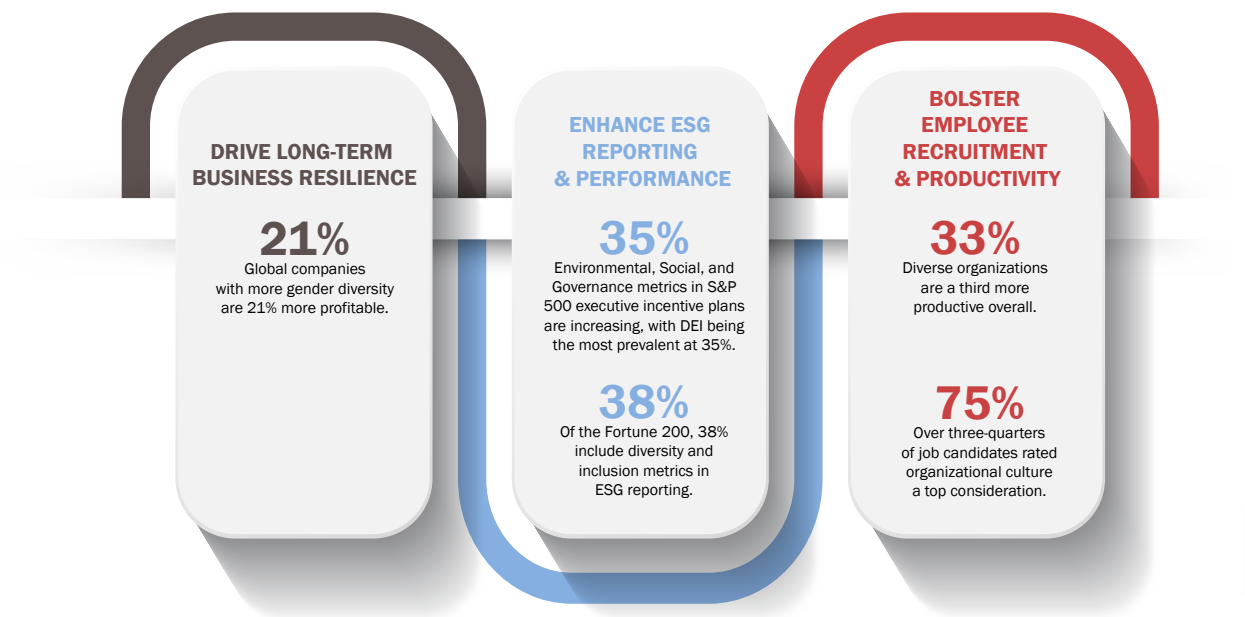

Resources and tools to help architecture firms seek equity in both their practices and processes continue to evolve. A recent Metropolis Think Tank Thursday panel discussion, “Building Equity in Practice and Process,” sponsored by Perkins Eastman, explored the topic with the firm’s PEople Culture Manager Emily Pierson-Brown and Director of Sustainability Heather Jauregui and International WELL Building Institute Chief Product Officer Jessica Rose Cooper. Led by moderator Avinash Rajagopal, editor in chief of the magazine, the panelists addressed ways to increase equity both within firms and across the profession, setting out a three-part strategy: build toward equity within the practice; embed equity values in the design process with clients and community stakeholders; and work within a framework to qualitatively and quantitatively assess goals and results.

Practice: Building Equity Within

“We want an inclusive profession because we don’t want to be gatekeepers for the work we do. We don’t want anyone to be harmed by the work we do. We want everybody to benefit fairly from the work we do,” says Rajagopal. Yet long marginalized groups remain underrepresented in the profession, even as architecture and design schools have made significant progress in recent decades. “We lead from the place where we are,” says Pierson-Brown. When we are surrounded by others who are similar in age, gender, race, and background, she notes, we create our own echo chamber. Seeking diversity and welcoming change within firms and professional organizations is integral to building equity holistically.

Heather Jauregui agrees. “We must start with ‘we’—the firm. Naturally, the more we talk about and focus on equity at the firm level, the more our designers will talk about and focus on equity in their work,” she says.

Equitable workplace culture manifests in many ways, prioritizing diversity in recruitment practices and providing flexible policies that accommodate individual needs among them. For example, one employee may need to pause or finish their workday at three o’clock to pick up children from school, while another may need accommodations throughout the week for regular medical appointments. “That kind of equity, where we’re looking at individuals and making space and accommodations for them in specific ways, is what breeds engagement among employees,” says Pierson-Brown, “and engaged staff members stay.”

Process: Building Equity Throughout

Opportunities to build equity are manifold through client and community relationships, consultant collaborations, material specifications, and other aspects of the design and construction process. “Our responsibilities don’t just stop at our front door. The work we’re doing everyday can and should contribute to a more equitable society,” says Jauregui.

Addressing equity in the design process, however, can be a sensitive matter. “A lot of clients are curious but fearful,” says Pierson-Brown. “DE&I for a lot of people is a minefield of ‘Oh my gosh, am I going to say the wrong thing?’” But, as architects and designers, Pierson-Brown says, “We are creative problem solvers. A big piece of creative problem solving is knowing which questions to ask. If we aren’t curious in this space, we’re never going to get beyond where we are right now.”

Pierson-Brown works in Perkins Eastman’s Senior Living practice area, where discussions around diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging are coming to the fore. “I’ve had really positive conversations about DE&I with clients,” she says. Currently, she is part of a team designing Opus Newton, an independent senior living community in Newton, MA, developed by 2Life Communities. Opus Newton is designed for residents in the middle-income market, and it is intentionally co-located with an existing low-income 2Life property, Coleman House, to create a mixed-income community. Amenities are spread across the ground floor of Coleman House, the new Opus apartment building, and a new centrally located “Connector” building to encourage community members to interact. This is also a key strategy to address some of the “us vs. them” mentality that can come with joining different socioeconomic groups.

The 2Life team has made a conscious effort to include Coleman House residents in the Opus Newton design process. For example, materials used to communicate various aspects of the project are printed in English, Russian, and Chinese so they can be understood by many. Feedback from the current residents is highly encouraged. The mixed-income project is a prototype to expand the housing options in 2Life’s portfolio and provide an operational, architectural, and financial model that could be replicated across the country.

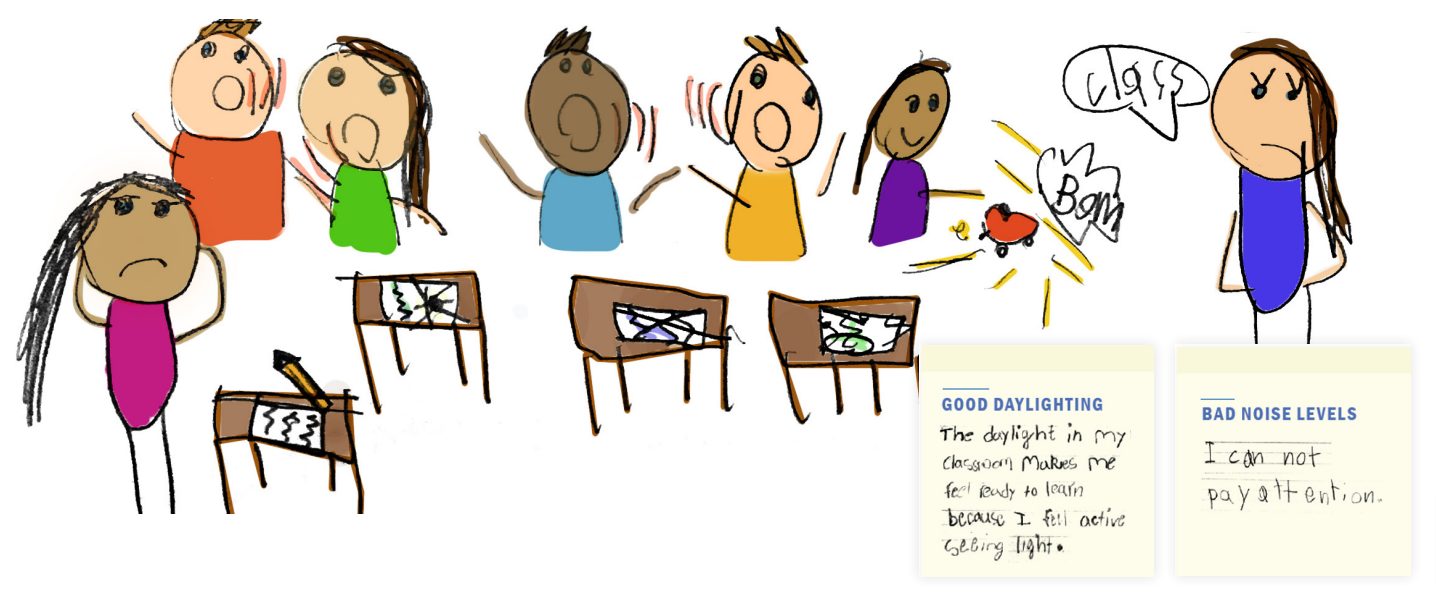

Jauregui provides another example—this one with an even broader potential impact. The District of Columbia Public Schools, a long-time client, accepted Perkins Eastman’s invitation to be part of the firm’s “Investing in Our Future” study to explore indoor environmental quality (IEQ) in modernized and non-modernized schools across the district. One part of the project measured noise levels in occupied spaces. The results showed that even recently modernized schools “were having issues with occupied noise levels and showed little to no improvement in occupied noise levels as compared to non-modernized schools,” Jauregui says. In part, the problem was due to existing acoustic standards, which were created more than 40 years ago at a time when learning environments were very different and few schools accounted for different types of learners (visual, kinesthetic, and auditory among them).

“Research shows that non-native language learners have an additional 28 percent reduction in comprehension at higher noise levels in classroom environments.”

–HEATHER JAUREGUI

Director of Sustainability at Perkins Eastman

At the time of the IEQ study, which was conducted between 2019 and 2020, Perkins Eastman had just begun modernization work on the district’s C.W. Harris Elementary School and used it to test current acoustic materials. To improve noise levels in occupied learning spaces, the team installed noise reduction coefficient ceiling tiles, acoustic tack board on walls, and acoustic panels on columns in two classrooms and in phases to determine the relative impact of one strategy over another. The test applications proved successful, and today the team is working to integrate these modifications throughout C.W. Harris and in other schools across the district. “This has equity benefits,” says Jauregui. “Research shows that non-native language learners have an additional 28 percent reduction in comprehension at higher noise levels in classroom environments. It really affects the non-native language learners at higher rates.”

Framework: The Triple Bottom Line

Equity is an integral, if not yet common, element of sustainable design practices. In fact, Jauregui asserts that the two—sustainability and equity— are inseparable. “We take a triple bottom line approach,” she says. “It’s not just looking at environmental value. It’s layering it in with social value and economic value. Equity comes into play at the intersection of these three categories.” Building materials and products represent one such intersection. From a strictly sustainable perspective, they should be free of harmful substances that off-gas toxic fumes and leach toxic chemicals into the environment. Their ingredients should be produced in a sustainable manner. And they should be packaged, shipped, and stored with minimal impact on the environment.

To help architects and designers assess and source the healthiest and most environmentally responsible materials, a variety of standards and lists are available: International Living Future Institute’s Red List, The Forrest Stewardship Council’s database, Products Innovation Institute’s Cradle to Cradle certification program, and Mindful Materials’ database, among them.

As Rajagopal underscores, however, global supply chains make specifying truly healthy materials a challenge. For example, nontoxic flooring products are healthier for users. But if their raw ingredients are processed in facilities that employ child labor, packaged in single-use plastic wrapping, and loaded onto diesel-burning ships and trucks, then their benefits are limited to the end user at the expense of vulnerable populations and the environment. From this perspective, Rajagopal says, “There’s no way to talk about carbon without equity. There’s no way to talk about health and toxicity without equity.”

The current push for solar energy illustrates this issue, Rajagopal adds. For instance, solar panels are created from a menu of rare metals, many of which are mined in third-world countries under highly inequitable conditions. Therefore, he says, “The health impact is not only on the people using the spaces and materials, but on the communities involved in the supply chain.” Solar power, wind power, tidal power, and nuclear power are fossil fuel alternatives that employ a similar supply chain. For comprehensive change, it is imperative that every aspect of the process is examined and pathways are identified that don’t exploit at-risk populations and deplete nonrenewable resources. Much work remains.

Framework: Guidance and Goals

Flexible work policies, diversity in hiring practices and leadership, healthy materials, inclusive community engagement, the global supply chain—striving for equity in process and practice can be an intimidatingly complex endeavor. To address this, Metropolis has created the “Design for Equity Primer: 20+ Resources to Help You Design Inclusively and Fairly,” a digital repository of articles and links to a wide variety of resources, including best tools for equity in supply chains, best practices for seeking diverse talent, and best processes for leading community engagement, to name a few.

One such resource has become essential to Perkins Eastman’s processes and internal practices—the AIA’s Framework for Design Excellence. The framework is arranged for teams to measure the impact of their work against 10 qualitative and quantitative principles: design for integration, equitable communities, ecosystems, water, economy, energy, well-being, resources, change, and discovery. “What the AIA Framework reminds us is that we need to be addressing all of these measures and advancing them simultaneously,” Jauregui says.

Developing and following a framework, whether through the AIA principles or other methods, helps teams make the biggest impact at the intersection of social, economic, and environmental sustainability. When creating guidelines, Rajagopal says, “focus on areas of overlap. Focus on strategies that can have multiple benefits.”

Jauregui concurs. “If we cut out the extraneous and zoom into design strategies that can have an impact across the entire triple bottom line, then we can get more bang for our buck. We’re able to hit all of our goals . . . by simplifying our approach.”

For firms looking to advance their internal DE&I goals, external ratings products and services can also be valuable. Resources and ratings include the International Living Future Institute’s JUST Label (Perkins Eastman’s DC studio is a recipient), the International Organization for Standardization’s ISO 26000, and the International WELL Building Institute’s WELL Equity Rating. The latter contains more than 40 measures spanning six impact areas: User Experience and Feedback, Responsible Hiring and Labor Practices, Inclusive Design, Health Benefits and Services, Supportive Programs and Spaces, and Community Engagement. Before selecting a rating system, however, WELL’s Cooper says, “We encourage our clients (and therefore architects and designers working with a client) to start by creating a DE&I assessment and action plan to reinforce the need for an integrative process.”

One of the differentiating elements of the WELL Equity Rating, says Cooper, lies in its flexibility. Companies with multiple offices using the rating system can pursue it on a location-by-location basis and tailor the strategies based on localized issues. “We are also encouraging organizations to think about this at scale,” she explains. To achieve effective results, the rating focuses on a bottom-up and top-down approach. “When you have engagement from employees as well as leadership, you have a better overarching outcome.”

Whether adopting an existing framework or rating system or creating new policies from the ground up, Rajagopal, Pierson-Brown, Jauregui, and Cooper agree that taking a small, even tentative first step is the best way forward. To make headway, Pierson-Brown suggests being both proactive and self-reflective: “Ask yourself, ‘What can I do now?’” N